![best wishes 1909 [800x528]](https://rivertonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/best-wishes-1909-800x528-300x198.jpg)

The scans displayed here are a diverse mix of greeting and travel postals received by from Clara from nearby and far away.

Plain non-pictorial message postcards for simply sending correspondence had been around for some time, but the first picture postcards in the United States began with the souvenir issues sold at the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Each postal had a picture and space for a message on one side, with the other side reserved for the address and cost only one cent to mail.

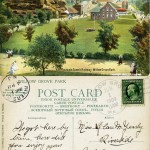

The card at right is from a time when postal regulations required that only addresses be written on the back of the card. The 1907 postal rule change which allowed “divided back” cards and writing on back launched the Golden Age of Postcards. Divided back postcards came along later in 1907, with the image on one side and, on the other side, a section for a message and another for the address.

The divided back postcards allowed for short messages, not unlike the text-based posts of up to 140 characters known as “tweets” posted by twitter followers today. Many vintage postcards have very short messages or none at all, and some are “postally unused,” having never been mailed.

Note the two postmarks on this divided back postcard. One postmark was imprinted when the postcard was mailed, canceling the stamp, and another was imprinted when the postcard was received. Do the math and you will see that the postcard left Willow Grove at 11 a.m. on Jun 1, 1909, and a mere five hours later landed in Riverside. Remarkable postal service for a penny!

Can any reader verify that back in the day (don’t ask me how far back) towns along the Delaware enjoyed two mail deliveries daily?

With the increased mobility brought on by the automobile, people traveled more and the penny postcards were an inexpensive alternative to telegraph or long-distance telephone rates for sending brief messages. Improvements in photography and printing technology, and the growth of a middle class with more money to spend on non-essentials are other factors that contributed to the picture postcard craze that exploded across America during the early 1900s. US Postal Service records show in 1908 that the population of 88,700,000 Americans mailed 677,797,798 postcards; that’s an average of over seven for every person!

Germany had a lock on producing the finest quality color lithography postcards until the onset of World War I curbed the civilian German printing industry. Most of this area’s superior color postcard views are consistent with this development, having postmarks before 1915.

In 1903 Eastman Kodak introduced a type of camera that enabled the public to take their own black and white photographs and have them printed on to postcard backs. Soon, Kodak and other manufacturers marketed more postcard format cameras, thus igniting the era of the real photo post card, or RPPC. Many RPPCs instead have a sepia tone, and they may, or may not, have a white border.

These unique cameras had a small thin door at the rear that could be lifted to allow the photographer to write a caption on the negative with an attached metal scribe. Inexpensive to produce at the time, these real photo postcard views can be among the most costly and sought after ones by collectors because of their one-of-a kind nature.

You can distinguish between a mass-produced lithography process printed postcard and a RPPC in a couple of ways. The lithograph process produces the image as little dots, but the photo image shows no dots when viewed closely. In a RPPC, the image has smooth transitions from one tone to another. In addition, older RPPCs sometimes show a silver sheen in the darker areas when viewed at an angle due to the silver used in the early photographic process.

The detail of the RPPC of Woodside Park in Pennsylvania at right exhibits this silvering in the darkest parts of the tree trunk above the swan.

During this time, just about any town appearing on a map had an array of hometown views to represent it. Riverton’s population was 1,788 in the 1910 US Census, and it easily is depicted in over a hundred unique postcard views of which we are aware so far.

A town with numerous postcards of its landmarks, parks and public spaces, schools and churches, government and civic buildings, business establishments, and such could promote itself as a good place to work, live, and visit to outsiders. Persons passing through the towns picked up the inexpensive cards as souvenirs of their travels as well as for jotting off a quick message to the folks back home.

![happy birthday 1907 [800x526]](https://rivertonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/happy-birthday-1907-800x526-150x150.jpg)

![Bird's -Eye View of Coney Island by Night 1906 [800x519]](https://rivertonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/Birds-Eye-View-of-Coney-Island-by-Night-1906-800x519-150x150.jpg)

![State Capitol, Des Moines, Iowa 1907 [800x514]](https://rivertonhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/State-Capitol-Des-Moines-Iowa-1907-800x514-150x150.jpg)

Readers and visitors, know that the Society is fortunate indeed to have received so many wonderful donations over the years from generous people who have helped enrich our understanding of Riverton history with their gifts.

The many gifts of artifacts, collectibles, ephemera, vintage clothing, and scans of collectors’ postcards related to local history all combine to help to better achieve our mission to discover, restore, and preserve local objects and landmarks, and to continue to expand our knowledge of the history of the area.

Today, as in days gone by, a spirit of altruism and civic-mindedness continues to be part of what it means to be a Rivertonian.

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have something you wish to add to this growing internet archive. We invite readers’ comments, corrections, and submissions of photos, articles, or research projects. – John McCormick, Gaslight News editor