By Mrs. Patricia Solin and John McCormick with research and editorial assistance by Paul W. Schopp

Note: This is an extended-play version of the article that appeared in the February 2012 Gaslight News. This column provides more space for explaining additional details and display of illustrations, photos, maps, etc, which the newsletter could not. We welcome your comments, anecdotes, photos, or corrections, to this article.

Note: This is an extended-play version of the article that appeared in the February 2012 Gaslight News. This column provides more space for explaining additional details and display of illustrations, photos, maps, etc, which the newsletter could not. We welcome your comments, anecdotes, photos, or corrections, to this article.

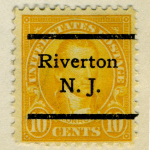

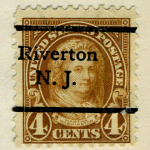

On July 30, 2009, the United States Post Office announced that 677 facilities would be considered for closing or consolidation, with 200 “most likely” to be actually closed. The Riverton branch of the U.S. Post Office escaped inclusion in that closure list and in several subsequent lists published since. We look back at the many changes to the borough’s postal service over 140 years as it operated from eight different locations.

According to the Historian of the United States Post Office, free mail delivery began nationally July 1, 1863. As long as postage would cover all the expenses of the service, the government established a post office in a community. By 1864, salaried letter carriers delivered mail in 65 US cities, although it only went only from post office to post office. Riverton, established in 1851, did not yet have its own post office in 1864. Rather, residents had either to pick up their mail in Palmyra or, as in other cities, pay an extra two-cent fee to a private local carrier for letter delivery.

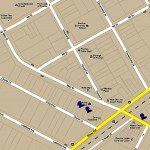

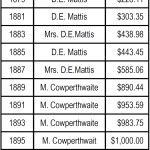

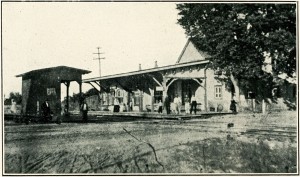

Riverton’s first railroad station opened in 1863 and once stood facing the tracks near Main and Broad, close to today’s site of the Riverton War Memorial. Charles Mattis, the railroad agent, lived in the house adjacent to the station at 601 Main, and served as Riverton’s first postmaster when the Riverton Post Office was established in 1871. However, borough residents still had to trek to the post office to pick up or to drop off mail. Mattis’ postmaster annual salary in 1872: a whopping $12.00! The house was razed in 1940 to provide space for the Riverton War Memorial.

Riverton’s first railroad station opened in 1863 and once stood facing the tracks near Main and Broad, close to today’s site of the Riverton War Memorial. Charles Mattis, the railroad agent, lived in the house adjacent to the station at 601 Main, and served as Riverton’s first postmaster when the Riverton Post Office was established in 1871. However, borough residents still had to trek to the post office to pick up or to drop off mail. Mattis’ postmaster annual salary in 1872: a whopping $12.00! The house was razed in 1940 to provide space for the Riverton War Memorial.

The job of postmaster was an important one–candidates for the job were proposed by the outgoing postmaster, the local community, or local congressional representatives. Beginning in 1836, the President appointed postmasters at larger post offices like Riverton’s as part of a spoils system. Often the position of postmaster was a sideline to their primary occupation, such as storekeeper.

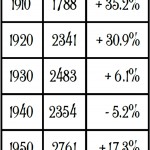

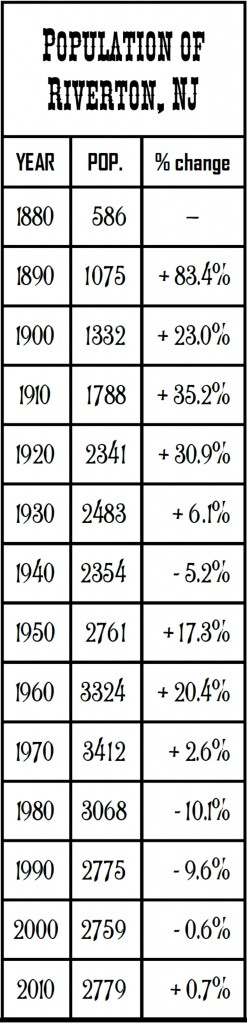

Those early days of Riverton were times of development and expansion, marked by population growth with each successive census, from its founding through 1930, and that certainly added to the volume of mail. No longer simply a summer refuge for wealthy Philadelphians, it had become a year-round community in need of a post office upgrade. Post office services over the years operated out of no less than eight locations along Main Street, including the railroad station, a drug store, shared space with an insurance office, what later became the office of The New Era newspaper, and a former bank.

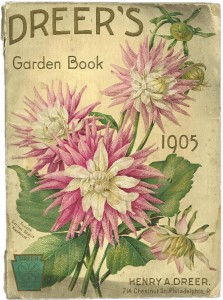

It is also quite possible, as some longtime Riverton residents attest, that post office capacity was influenced through a literally growing business: Dreer’s Nursery. In 1873, Henry Dreer moved his nursery business from Philadelphia to Riverton. Employing over two hundred workers in-season, the company was the largest employer in town. Comprising about 100 acres of seeds and plants, and eight acres of greenhouses, the highly regarded House of Dreer demanded a quick and efficient way to mail their delicate products nationally and internationally. The thriving business eventually expanded to 295 acres with a water garden and 14 greenhouses with palms, ferns, bamboo, irises, and hybrid waterlilies.

In a paper presented at a symposium at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in 2006, author Dr. Cheryl Lyon-Jenness credits improvements in the postal service that accommodated industrial needs for fueling the horticultural boom during the nineteenth century. The fortunes of many prominent nurseries and seed companies benefited from their close proximity to population centers and transportation hubs, the firm of Henry A. Dreer among them.

In a paper presented at a symposium at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum in 2006, author Dr. Cheryl Lyon-Jenness credits improvements in the postal service that accommodated industrial needs for fueling the horticultural boom during the nineteenth century. The fortunes of many prominent nurseries and seed companies benefited from their close proximity to population centers and transportation hubs, the firm of Henry A. Dreer among them.

However, to what degree the Dreer mail-order business affected the post office and mail volume cannot be determined. Numerous periodical advertisements over many years always required the respondent to address their request to Philadelphia headquarters, not Riverton. A 1916 Dreer’s Garden Book promised, “We deliver postpaid to any Post Office in the United States, Vegetable and Flower Seeds…” It also boasted of “… an eight-story warehouse at 710 South Washington Square, which affords ample storage facilities and room for the careful and prompt filling of orders.”

However, to what degree the Dreer mail-order business affected the post office and mail volume cannot be determined. Numerous periodical advertisements over many years always required the respondent to address their request to Philadelphia headquarters, not Riverton. A 1916 Dreer’s Garden Book promised, “We deliver postpaid to any Post Office in the United States, Vegetable and Flower Seeds…” It also boasted of “… an eight-story warehouse at 710 South Washington Square, which affords ample storage facilities and room for the careful and prompt filling of orders.”

The 1938 Hundredth Anniversary Edition of Dreer’s Garden Book displays photos of an order-filling department and a mailing department, which appear to be housed in the even larger 1306 Spring Garden Street address, which the business had occupied since 1924. Further, of twenty-two examples of postmarked Dreer postcards and one letter in our collection, seven have Riverton postmarks, and the rest are from Philadelphia. The assertion of our forebearers notwithstanding, lacking figures that would break down what goods or correspondence were dispatched from where we cannot determine the impact that the Dreer’s seed and plant mail-order business had on the Riverton Post Office.

In 1887, when the first railroad station had proved inadequate, a larger brick structure at Broad and Main replaced it, across from where Zena’s Patisserie shop is today. Apparently, the post office remained in the house at 601 Main, where Dorothy Mattis had already assumed the duties of postmaster beginning in 1876. In 1888, the post office moved to Cowperthwaite’s Drug Store at 304 Main, where proprietor Milton Cowperthwaite doubled as postmaster. There was still no home delivery for Riverton, however. Postmaster Cowperthwaite’s pay, which was based on volume, had jumped to an even $1000.

Realize that in those early days of Riverton’s development, the railroad station was on the edge of town, making it inconvenient for those who walked to pick up their mail. The move to Cowperthwaite’s in the 300 block of Main made it a more centrally located post office.

Oddly, rural families living in the area enjoyed home delivery of the mails even before homes within the borough did. An experiment in delivering mail to rural districts commenced in February 1898. Twice a day, carriers picked up incoming mails from Cinnaminson and Riverton and traveled two routes along New Albany, Parry and Lenola roads, and old Burlington Turnpike, now U.S. Route 130.

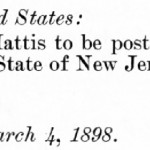

In March of that same year, the U.S. Senate recorded President William McKinley’s nomination for the postmaster position. Stewardship of the post office then passed to Ogden Mattis, son of Dorothy and Charles Mattis, and the venue for postal operations moved to 520 Main Street (now the Presbyterian Thrift Shop). The Rural Free Delivery service became permanent in July 1898.

The diligent postmaster reported on the situation of the new rural delivery service to the United States Postmaster General in October 1898:

The general sentiment of the people is of extreme satisfaction, and they are unanimous in desiring its continuance. There are two other communities in this vicinity that desire the establishment of rural free delivery. The amount of mail matter handled by the rural carriers has increased each month.

R. M. Brock, a local beneficiary of the improved service who lived two miles from the post office wrote, “I do not know how to express myself for the benefit that I have already received.”

E.S. Holmes concurred:

My neighbors, as well as myself, regard rural mail delivery as the greatest privilege we enjoy. I have not heard anything but praise for the service and would be very sorry to see it discontinued. Before it was started here, to mail a card even, I had to hitch a horse and drive a round trip of 4 miles to the nearest post office.

Clayton Conrow of Cinnaminson added his praise in a letter:

I know of no act of the present Administration which has so warmed the hearts of the people who receive the benefits of it, irrespective of political affiliations, as this free rural mail delivery.

Due to the increase in daily mail volume and stamp revenue generated by the facility, Riverton Post Office advanced from third class to second class in 1901. The US Postmaster General’s Report for that year recorded $1,800 for the Riverton postmaster’s salary. Since the volume of mail helped to determine the postmaster’s pay, enlarging the postal service area and accommodating customers was a win-win for the local postmaster.

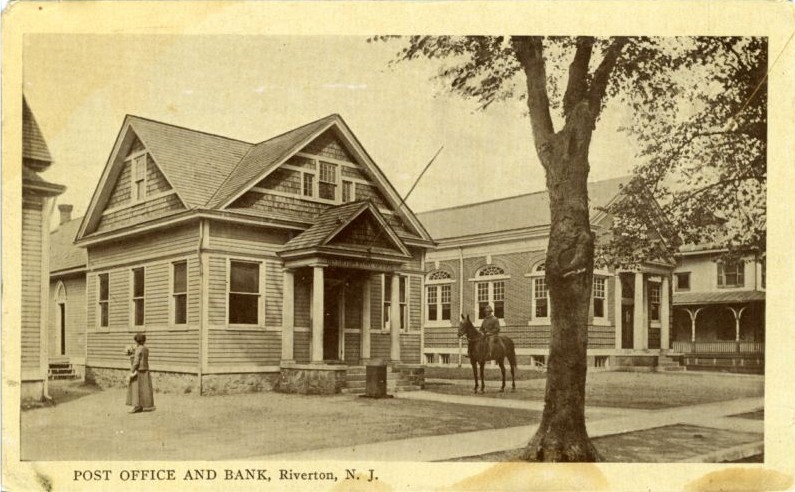

During the ten-year tenure of Ogden Mattis, the post office again outgrew its space at 520 Main and leapfrogged over to a new building at 528 Main Street, which opened on February 19, 1903. That day’s Philadelphia Inquirer proclaimed:

For the first time in its history, Riverton has a post office building. The office has been at various times in the station, grocery store, and a shoe store. The great increase of business in the last four years has made it necessary to provide a building specially adapted for post office purposes.

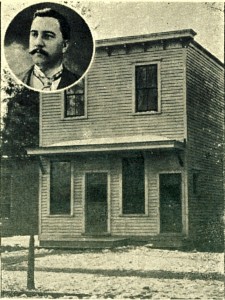

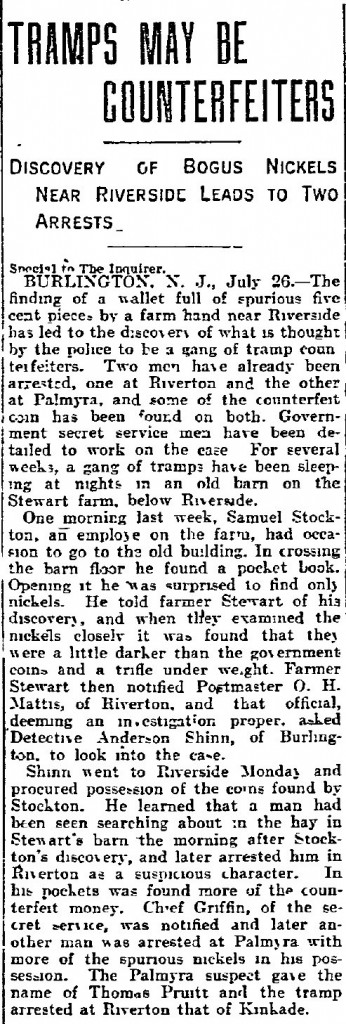

While postmaster, Ogden Mattis found himself on both sides of the law in Riverton, and by all contemporary accounts, his standing in the community likely improved in both cases. In July 1904, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported that he had helped foil a ring of tramps staying at a farm near Riverside who were passing counterfeit nickels. The cost of the newspaper that day: one cent.

Normally, taking a few sick days would not make the newspaper, but one Riverton rural mail route carrier made the pages of the Philadelphia Inquirer when he fell ill and needed a substitute to handle his appointed rounds. The headline read, “Wife Took Husband’s Mail Route.” Whatta gal!

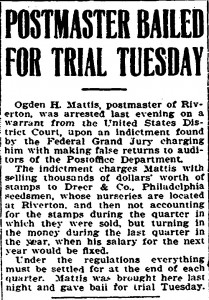

Riverton citizenry must have been shocked indeed in June 1906, when a federal grand jury indicted their crime-busting postmaster for “…making false returns in 1904 and 1905 to the department for the purpose of increasing his compensation.” It found that he had violated postal regulations by selling thousands of dollars’ worth of stamps “to a Philadelphia firm” and then not turning in the money for them until the last calendar quarter—the one which determined his pay for the next year.

The Philadelphia firm, of course, was that of Henry A. Dreer. Mattis pleaded “not guilty.” The Philadelphia Inquirer reported on June 25, 1906, “…he was brought here tonight and gave bond for trial next Tuesday.” Perhaps in support of his cause, the editorial page of the Philadelphia Inquirer quipped on June 26:

Postmaster Mattes (sic), of Riverton, has come to grief doing too much business for Uncle Sam; which teaches that a good businessman should not waste his energies in a postoffice.”

A July news dispatch pushed the trial into September, but it appears that the trial may have had further delays. Despite being under indictment for fraud, his postmaster’s salary rose to $2,100 in 1907. Inexplicably, the matter was not resolved until May 1908, as his commission was nearing its end.

As described in the May 14, 1908, Trenton Evening Times newspaper account, when two US District Court judges passed sentence of a $400 fine on Postmaster Mattis, “…at least 50 friends of Mr. Mattis who were in the courtroom to testify as to his character, gathered around him, and practically all of them offered to pay the fine.” Presumably, some of these were buddies from the Riverton Firehouse, Riverton Gun Club, Republican Club, Masons, or Riverton Yacht Club—all organizations with which he had ties–or perhaps even some employees from Dreer’s.

The real head-scratcher is that the one who ultimately wrote out his personal check to cover the fine was Thomas J. Alcott, the very United States Marshal in whose custody Mattis had been. Central to Mattis’ defense was his argument that he had made the false returns to keep his post office out of the carrier class, not for personal gain. Another factor that helped him in receiving the relatively mild sentence was that he had deposited the money in the post office account at the bank. In this light, an inclination to ascribe the best motives to his alteration of the office’s gross receipts is understandable.

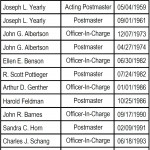

Charles L. Flanagan assumed postmaster’s duties in May 1908, right before another upsizing. In 1909, the post office service migrated back across the tracks, this time to 609 Main Street (the current place of business for Freddy’s Shoe Repair), a small frame building, next to what was then the Cinnaminson Trust Bank. In addition to Charles L. Flanagan, three more postmasters each served terms as postmaster there: Horace G. Stonaker (March 1917), Ross E. Mattis (Feb. 1922), and Mrs. Mervil E. Haas (June 1934).

Nine thousand pieces of mail passed through the post office per day in 1909. Two postal carriers covered about twenty miles on their rural routes, twice each day (except on Sunday) to over 210 families, delivering 800 pieces daily. Riverton had the only post office between Burlington and Camden open on Sundays, with nine mail shipments arriving and departing daily by train. However, Riverton residents still had to trek to the post office to pick up their mail.

Home delivery in Riverton finally debuted November 1, 1922, as it cleared the last obstacle that had blocked it for so long—the establishment of standard house numbers within the borough. Riverton had long before satisfied the other requirements of the 1863 Act of Congress that provided for free mail delivery such as providing sidewalks, named streets, and street lighting.

Meanwhile, in 1928, the Cinnaminson Bank moved across the street to their new larger quarters on the corner of Main and Harrison Street (now the location The Bank on Main, an event venue owned by the Antonucci Family). In April 1936, the old bank at 611 Main served as the next location in this growing succession list of Riverton Post Office sites, with the former post office at 609 Main becoming the new office of Riverton’s hometown newspaper, The New Era. Riverton resident Joseph Yearly started his 37-year postal career in 1936 at 611 Main under Postmaster Haas. He recalled that the office employed eight men servicing two deliveries a day in town. A Model A Ford was used for the rural route into Cinnaminson.

Postmaster Mrs. Mervil E. Haas holds the Riverton record, discharging her postmaster’s duties from three different Main Street locations spanning the years 1933-1959. She served the greater part of her career in the next and most ambitious upgrade of all Riverton Post Offices.

Postmaster Mrs. Mervil E. Haas holds the Riverton record, discharging her postmaster’s duties from three different Main Street locations spanning the years 1933-1959. She served the greater part of her career in the next and most ambitious upgrade of all Riverton Post Offices.

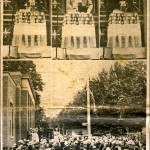

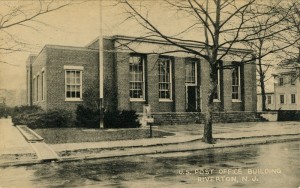

The Riverton Post Office at 613 Main was one of 29 building projects authorized by the Postmaster General and the Secretary of the Treasury for construction in the State of New Jersey by the Emergency Relief and Construction Act of 1932. The Riverton July Fourth festivities agenda in 1940 included a dedication ceremony for the long-anticipated new post office facility built expressly for the United States Post Office Department by the Federal Works Agency at 613 Main Street. This new building was one of over 1,100 post offices that the federal government built during the New Deal.

World War Two intervened and interrupted Mr. Yearly’s postal career from 1942-1945. With the return of GIs after the war, population growth in post-war Riverton and elsewhere created the Baby Boomer demographic, and in 1947 the Riverton Post Office was hiring to fill new substitute clerk-carrier vacancies. Starting pay: $1.04 an hour.

Joseph Yearly eventually rose through the ranks to become Assistant Postmaster and succeeded Postmaster Haas in 1961. Over the years, he had seen the cost of mailing a letter increase from three cents to ten cents, and the office grow to service 17 routes.

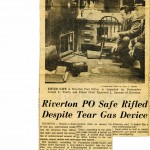

Mr. Yearly was at the helm when safecracking thieves twice broke into the Riverton Post Office at 613 Main Street. The first time, in February 1964, netted the burglars nothing, but they damaged a vault that held street letter box keys, so the headline read, “Not Rain Nor Sleet But Key Stays Mail.”

Four years later, a safe now fortified with tear gas did not deter another thief from cutting a 24-by-30-inch hole through the door of the safe with an acetylene torch and fleeing with $25,000 in stamps.

Joseph Yearly retired in 1974. What he did not know then was that Riverton’s years of growth and development were largely behind it, that declining population was in store ahead and downsizing was all but inevitable.

In November 1991, all offices and carrier services transferred to the newly constructed “state of the art” Cinnaminson facility, just off Route 130 on Andover Road. In an unusual turn of events, the Cinnaminson Post Office remained a branch of the parent Riverton Post Office. The Riverton site continued to maintain counter services and 250 boxes.

This transfer of carrier operations to Cinnaminson only foreshadowed further reduction of services for the post office. Finally, over Memorial Day Weekend 2009, Riverton’s stately post office at 613 Main relinquished all mail services to a diminutive postal facility that opened at 605 Main Street, part of Riverton Square, LLC.

That imposing edifice (below) that dominates Main Street is the Riverton Post Office that is familiar to the memories of most Rivertonians, operating for almost seven decades. Many consider its closure a loss, representing more than merely a cutback in services. The shuttered federal building was a blow to Riverton’s civic identity that they did not see coming until it was too late.

Riverton officials, anxious to move municipal offices from their cramped location in the Borough Hall to a larger building, considered the possibility for a time but abandoned the idea as impractical. The property languished for months in the doldrums of the commercial real estate listings. Ultimately, a local developer rehabbed the vacant building and it subsequently became the place of business for Tristate HVAC.

Manager James R. McQuaide now conducts business from the postmaster’s office. Still not settled into his new digs, he explained during an impromptu tour how postal supervisors could look down on the sorting area undetected through viewing slots accessible from an upper-level room. Mr. McQuaide seems elated at the opportunity to base his company’s operations in such a spacious and historic building.

Out in the back of the old post office, even the huge parking lot where mail trucks once pulled up to the loading dock has been downsized. BWC Realty Associates, LLC carved out three building lots for residences at 608, 610, 612 Cinnaminson Street, still leaving Tristate HVAC ample parking and loading access.

The contrasts between the post offices at 613 Main and 605 Main are astonishing and give some residents pause to wonder what further cost-cutting measures will bring. Will twenty-first-century downsizing threaten to return our post office from whence it came–relegated to being a sideline business for a storekeeper.

Over the past two years, hundreds of post offices have closed across the nation as the Postal Service system shrinks in an effort to cut costs. We shall not debate here the many complex reasons for the postal service’s financial crisis. Clearly, the universal postal service envisioned by Benjamin Franklin is in jeopardy as events play out which threaten the very “special delivery” that we have enjoyed from our many post offices over the years.

Special thanks to Mrs. Mary Yearly Flanagan for making available her family albums and files of newspaper clipping, photos, and information, without which the story of Riverton Post Office would have been incomplete.

We welcome your comments, contributions, and corrections.

Please contact: John McCormick, Editor

The Historical Society of Riverton

Post Office Box # 112

Riverton, NJ 08077

E-mail:rivertonhistory@usa.com Web: rivertonhistory.com/

Evan Kalish has been GOING POSTAL since 2008, but in a good way, visiting over 3,000 USPS facilities and writing a blog that has drawn international attention. In January 2012, he visited post offices at Palmyra, Riverton, Cinnaminson, and Riverside one afternoon. Go along for the ride at – colossus-of-roads.blogspot.com